Add It Up

Today, another rant about a Newsweek column; this time, it's not Anna Quindlen, but the topic is definitely strongly related to feminism.

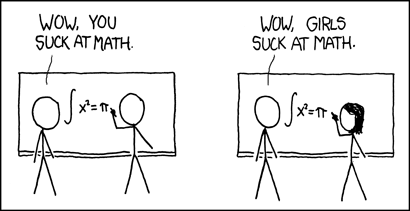

Sharon Begley, Newsweek's science columnist takes a moment to speak up on a subject near and dear to my own heart: sexism and stereotypes about learning ability. ("Math is Hard, Barbie Said") See, just in case you're not aware of it, American girls have a hard time with math, generally finding it too challenging for them, and thus we find that there is a clear gender gap in ability and achievement in this area. The thing is, though, it's all (as they say) in their minds.

I love parenthetical statements, don't you? (Okay, maybe it's just me.) "As they say" is really the operative phrase here. The fact is, while girls in America and Japan have consistently lagged behind men in mathematical ability, that gap has been far narrower in communist nations where supposedly they take a more liberal view of the ability and worth of the individual, regardless of gender. It would seem--and to many of us, there's no surprise to this--that girls do badly in math because society has told them that they will have this failing.

The result, according to Begley is something more than simply a self-fulfilling prophecy of "Tell somebody they can't do something, and they probably won't be able to do it," but actually an emotional response. Tell a girl she can't do something, and even if she doesn't believe you, the fact that you gave her discouragement will cause a distracting emotional reaction. How well are you going to be able to focus on factoring a polynomial when half your brain is screaming out to you, "How DARE they say that!"

This fact is very personal to me for two reasons. One of them is that despite that my degree is in mathematics and I know I tend to be very good at it, there was a time around fifth and sixth grade when I struggled with math. I had a couple of math teachers who, instead of encouraging me to do better, essentially took time and effort to embarrass me and tell me I was a failure. I never considered the fact until just now what a boon it was for me to have a seventh-grade math teacher who was completely incompetent. I've always wondered how a guy like that ended up teaching math when he obviously had no skill in the subject, but in retrospect, I wonder if it helped stroke my ego to recognize that my own ability was better than the teacher. (This was the first of many teachers that I had the habit of viciously correcting on a daily basis, pointing out his errors at every opportunity, which came frequently. On the same note, it was probably oddly useful for his ego that he clearly just didn't care.) I realized long before seventh grade that mathematics was the method of understanding reality on a basic, foundational level, and seeing it taught with such ineptitude goaded me into always being the best I could be.

But I was lucky. As a boy, when I showed ability in math and science, society approved and egged me on to greater achievement. The second thing that's always bothered me about this topic, and this one even more so and more repeatedly at every chance it had to come into my mind, was the fact that my sister did not go into a college major in math or science. Sure, all things being equal she might still have chosen the path she did, and I'm not aware of any regrets on her part; she's been very successful in the things she's set her hand to as far as I am aware. What irks me is that I do feel she was shorted in the area of praise for her abilities. I became the math major in college, I was the one that people actually called a "math genius" repeatedly in high school. (Note that when you go to a small-town high school, and then graduate to a large university, you tend to find that most areas where you were considered excellent are now areas in which you are merely average; I don't claim to be anything special today.) Nobody ever called my sister a "math genius", but I always suspected that she was far superior to me.

Once when visiting home from college, I was rummaging through some papers in my mother's house, and came across some standardized test scores. A test taken sometime towards the end of elementary school revealed that while I was above average in my mathematical aptitude, my sister was truly the cream of the crop. Yes, my sister was the real "math genius", but where did that genius go? Fast forward from elementary and rewind from college to the beginning of my senior year. This is the time that you start looking at your grades and test scores and pick what schools you want to look into. The school guidance counselor called me into his office and informed me of what was supposed to be great news. I knew my SAT scores were good, but apparently, in my small rural county of Northern California, I had set the record of highest-ever SAT score. I might have reveled in that announcement if it weren't for the very following sentence with came before the first had a chance to sink in.

"And the person who previously held the record was your big sister!" I was told with a big grin. How about that, Brucker? Consider the irony! Oh, I did.

"Uh... Was my sister informed when she had set the record in the first place?" I asked. "This is the first I've heard of it."

The smile disappeared. "Um, well, I guess not."

"Why the hell not?!" I responded through gritted teeth, and I got up and left. I was always somewhat aware of the problem, but that day, it hit home in a special way. Friends come and go, but my sister will always have a special place in my heart, and I couldn't forgive the injustice done to her or to all our sisters everywhere. As I said, I get the impression that my sister was satisfied with the academic course her life took her on, but I can't help but feel that nonetheless she was robbed of a full set of options.

Thus comes the real problem, the larger problem as I see it. Sexism and racism aren't just bad, but hurtful things that cause often nearly irreparable harm. Our society is closing down gaps all over the place, but will the wounds of the past ever be healed? Within a few months, it appears we will likely have our first black President, but will a single black President make up for centuries of slavery and oppression? When the day comes that a woman is placed in the Oval Office, will that make up for all the years they were treated as slaves in attitude, if not in name?

Prejudice says, "We're not going to allow you to be equal." When pressed, it says, "Okay, you can have the right to be equal, but you will never really be equal." Eventually, after centuries of beating down the oppressed, be they members of a race, gender, or other social group, the members of the oppressive group ask the oppressed group, "Why are you so bitter about all that stuff? It's in the past!" There is a tendency to miss the fact that the fight against oppression is an uphill battle, and even when the playing field is leveled, it's hard to shed the weight of the past.

When Begley points out that the very fact of being told that you can't do something impedes the brain from doing it, she points out that it doesn't have to be personal. A girl doesn't have to be told that she is incompetent in mathematics, she need only be told that historically, women have underachieved in comparison to men, and the discomfort that sets up in her mind is sufficient to impede her thought processes. This is the sort of thing that goes beyond self-worth, and turns into an evaluation of the worth of the group to which one belongs. We tell people that they are inferior for long enough, and some of them believe it; among those who have the determination to not believe it, more than a few will still be burdened by the injustice of the sentiment.

You don't have to be a member of an overtly downtrodden group to experience this for yourself. Think about the situation we have here in America with respect to the learning of foreign languages. There's a joke I've heard a few times that goes like this: "A person who speaks two languages is called bilingual; a person who speaks three languages is called trilingual. What do you call someone who speaks one language? An American." Why is it that Americans have such a hard time learning foreign languages, but so many Europeans and Asians seem to typically speak three or four languages? I know Americans in general won't accept the argument that these people are somehow intellectually superior to us. I personally believe that we as Americans don't learn foreign languages because we've decided it's just too hard. This is not something indicative of any subset of the culture of the United States, but seems to pervade us in general. We either believe that we just can't do it, or we think we might be able to, yet we look around and note that few people are doing it and get discouraged. This isn't even the result of anyone acting prejudicial towards Americans, but merely a culture that has shifted into a sort of self-prejudice. Imagine if it were a matter of prejudice; instead of simply struggling through your language classes worrying about how difficult it is to conjugate verbs and learn the gender of nouns, you also have to keep thinking about how everyone's expecting you to fail.

But here's where my cynicism cuts in and takes over again. Begley points out that things are getting better for women, and they are beginning to be accepted more often as the intellectual equals of men, but will equality--true equality--be realized in our lifetime, if ever? If we as Americans can slip into a feeling of hopelessness over our inability to acquire languages without any sort of external oppression, how can people who have been actively pushed into a state of hopelessness rise above it? Perhaps asking such questions is largely adding fuel to the fire, but it needs to be said anyway.

I don't believe that we escape the evils of the past by simply trying to forget that they ever happened. We escape from them by actively fighting to overcome them. As a father of two daughters, there's a significant battlefront of this culture war located within my own household. It's a hard responsibility that's been given to my wife and me to see to it that our daughters are never told that they are any less capable of anything simply because of their gender. Really, that's the only thing we can do: try our best to raise up a new generation better than the past. Do we do this by never mentioning the sins of past generations towards their mothers and grandmothers, or by entreating them to actively strive to overcome the vestiges of that shameful past? I don't know the answer to that. Maybe it would take a woman to figure it out?