Trump’s America

There are a lot of people, probably mostly liberals, who are really quite shocked to find us where we are in America today. How did a terrible man like Trump become our President? This is not who we are as a country!

I think this sort of thinking requires a denial of the reality of United States history, both in the long view and in the more recent. Trump is, in many ways, the quintessential American President. Trump is America with the mask of politeness taken off and discarded.

Perhaps the most obvious thing about Trump that is so American is the racism. While we love to think of America as the "melting pot" of cultures, we're a nation pretty much founded on white supremacy. We were created by the genocide of indigenous Americans, and built by the forced labor of people stolen from Africa. The White House (so appropriately named) itself, the home of our nation's leader, as pointed out not too long ago by Michelle Obama, was built by slave labor. I myself am fond of reminding people that the founding fathers were made up of two groups: rich white men who loved Black slavery, and rich white men for whom Black slavery wasn't a deal breaker.

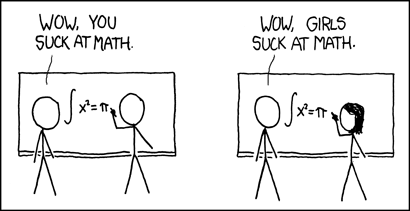

Trump’s sexism is also very American. We became an independent nation in 1776, but women weren't federally given the right to vote until 1920, nearly a century and a half later. (Oh, and that was only white women, of course.) And voting is just one right of many denied women; the right to own property, the right to have a bank account separate from their husbands, the right to not be discriminated against for employment or housing? All of those came later. Of course, one of the most important rights, the right to be able to control their own bodies and their reproductive choices? That one's still up in the air, as women are effectively given less bodily autonomy than a corpse.

What else defines Trump? Xenophobia? I would call it selective xenophobia, as ICE raids places known to have immigrants with black and brown skin, but makes no moves against communities of undocumented white immigrants. We build a wall on our southern border, but largely ignore undocumented immigrants coming across the northern border. Why? Well, those immigrants are white, aren't they? I may be wrong, but I believe the very first law in the United States limiting immigration was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, because we can't have non-Europeans in the U.S., can we? Of course before that, when the United States won a large portion of the southwest from Mexico in the mid-19th century, Mexicans in those territories were assured on paper that they would be American citizens, but apparently in practice, most of them were driven off the land, deprived of property and rights. America has never been keen on accepting non-Europeans, so Trump’s xenophobia is really nothing new.

Oh, and putting the rights and needs of rich people over those of the poor and middle class? That's just capitalism, which has also always been us. White capitalists have always ruled this country, and pretty much every President has been at least a millionaire. Bigotry against LGBTQ people? That's a western cultural norm. We used to (really still do) have laws against them existing, and barely have half a century of progress towards equality, but conservatives will constantly make up stories about how drag queens and transgender women are attacking children despite the fact that the observed reality is that the people children have to fear are religious leaders and their own parents.

This unfortunate conglomeration of lies and bigotry is what America is, has always been, and it's that reality that Trump represents. Can we change? I hope so, and so do many other Americans. But no politicians from either of the two major political parties seem to be willing to make those changes. I believe it's going to take a major shake up of the status quo that's going to require either some restrategizing in the Democratic party, or a rejection of the outdated Democratic party for a newer, more progressive set of politicians. Really, it may take a revolution of some sort, because the status quo needs to be completely rejected, and that's hard to accomplish.

If you, like me, don't want Trump’s America, then don't wait for voting in the midterms in 2026. Start strategizing now, and pushing for changes that can happen now. It's going to take a fight to reverse 250 years of history, but it's not impossible if we put in the work.