"Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." -Arthur C. Clarke

I think I've finally figured out the problem with science. That is to say, I think I know what the real issue is with the public perception of science, and what it is about it that makes the average layman surprisingly loath to trust it. Let's face it; every day we're going to open the newspaper and find another story along the lines of some school board refusing to teach evolution, and the more "enlightened" among us will shake their heads and mumble something along the lines of, "Are we living in the dark ages or something?" Well, I've decided that in the end, the problem surprisingly lies with science itself, and the manner in which science by its very nature generates its own bad press.

I don't remember what it was that was simmering somewhere on the back-burners of my mind the other day as I was perusing some essays by

Isaac Asimov, but maybe it will come back to me, as it had become a thought suddenly boiled over when I hit a particular sentence in one of his essays. Just in case you're not familiar with Asimov--and actually, you're probably not as familiar as you think you are even if you do know something about him--he's probably best known as a science fiction writer, but also carried on his resume a number of works of fiction in the genres of mystery and fantasy, as well as a certain amount of writing on science fact, history, and Biblical commentary. Asimov was probably my favorite author as a child, and I'd always wanted to write as well as he did, but never thought it likely. Turns out my wish may have come true: while his storytelling is superb, his essays are pretty crappy. I am in good company after all.

It's probably actually not his essay writing overall, but this particular subset. I picked up a copy of

Magic: The final fantasy collection, which is a gathering together of all Asimov's "fantasy stories that have never before appeared in book form." Truth be told, even the fiction is not quite as good as his sci-fi works elsewhere, but the section of essays dissecting the

nature of the fantasy genre seem to really fall short. Maybe it's just me. Actually, one of the hard things in evaluating the fiction is that not too much of it falls into the standard sort of format that one thinks of as "fantasy"; one story, a mystery involving Batman, actually has no supernatural element to it at all, so go figure.

What does all of this have to do with

science, though? Well, as Asimov works his way through essay after essay of reflection on the subject of magic, faeries, mythical creatures and dashing knights riding off to slay dragons, he ends up--as a firm believer in science, and an author with a strong preference for science fiction over fantasy--taking many of these thematic concepts and relating them back to scientific principles. Science fiction and fantasy both generally involve the use of extraordinary means of meeting the protagonist's ends, but there tends to be a divergence in the nature of the means that is sometimes hard to describe precisely due to the fact that, as Clarke has said, technology can sometimes

appear to be magical. Asimov points out that the real difference is that technology is something that always comes with limits, but magic much less so.

An excellent example is to think about the worlds of "Star Trek" vs. "Harry Potter". Both involve fictional means of teleportation, but there are few similarities in the workings of each. In the Trek world, teleportation is made possible through the employment of

technology that requires a very large amount of energy and powerful supercomputers. Those attempting to teleport with these devices need to program these powerful computers with the particular coordinates of departure and arrival, the subjects of teleportation cannot be in motion, the teleportation device must be fully-powered and within a certain distance, and (for some unstated reason that has never made much sense to me) the operator of the device needs to know the number of people being teleported. In Potter's world on the other hand, all one needs to

teleport is to be a wizard who really wants to go to a location in mind. I'm sure there are Potter fans who would take issue with such a simplification of the process, but really, I've simplified the process from both worlds.

So who is the winner? Maybe it seems like Potter is, as he needs no power source or help from a computer, has no limits on distance of travel, and can disappear at will in mid-stride while running from the hot pursuit of Voldemort. Not so, however. There are, and will always be, people who have a preference for the theoretically possible over the fantastic. After all, what good is Potter-style teleportation to "muggles" like you and me? Computers and technology, on the other hand, make amazing strides daily, and who knows? While physicists haven't yet invented the warp drive, it has been suspected that the principles of relativity actually do allow for travel

faster than light speed if we could find a way to manipulate the space-time continuum. Sci-fi has a lot of big "ifs", but they're not the ridiculous imaginings of magic and fantasy, at least.

That sort of thinking is actually the smaller part of the problem of science: it's sort of a killjoy. On page 143 of "Magic", Asimov points out that the old fairy tale staple of "seven-league boots" are something for which science can't really produce an analogue. Seven-league boots are magical pieces of footwear that allow the wearer to move seven leagues (21 miles) in a single step. Asimov points out that such boots would cause the wearer to, at the pace of a brisk walk, achieve escape velocity and therefore be launched into space in a stride or two.

Sheesh, Asimov, you're no fun. I'm not personally a big fan of the fantasy genre, but I think it's clear enough that we're meant to understand that magic boots, by the very fact of their being magic, don't have to concern the wearer with mundane factors such as escape velocity and wind resistance (I'm sure someone could give some very good reason why travelling at escape velocity with no protective gear would cause air friction enough to vaporize you, or at least severely chap your skin). Asimov is only trying to point out that science, unlike magic, has limits, but really the depressing thing about science is that really on the whole, science is all about telling us repeatedly that we are

limited.

One of the best-known limits in science is the speed of light, but it's odd that it's so well-known. That is to say, it's not that people know

what the speed of light is (I can seldom remember it off the top of my head), but they know it

exists, and the one thing they really know about relativity theory is that things in the real world can't go faster than light. What does this really do for the layman, though? What possible purpose does it serve the non-physicist to know that the universe has a speed limit, especially since not a one of us will likely ever travel so much as 0.01% of that limit? It only reminds us that we do not have unlimited ability, and while this is true, it adds nothing to the human condition to know it to be so. Science doesn't care, nor should it, as it exists in a world of

facts and not

fantasy or

feelings.

I've written before that science is not in the business of making people feel good or have a sense of self-worth, and that's why it makes for a lousy religion. "But wait," most readers will object, "science isn't a religion!" No, it's not. The bigger part of the problem of science is that despite that fact that it isn't a religion, there are an awful lot of people who

treat it like one. Something else that I know

I have written about many, many times is the fact that the world is full of skeptics who are more than happy to puff out their chests and declare, "We don't need God and religion to give us the answers, for science has all the answers we need!" But whatever you may feel about religion, the second part of that sentence is dreadfully wrong: science doesn't have

answers, it only has

theories. Wait! I'm probably not saying what you think I'm saying...

My imagination makes it hard to write this, as I know with almost every sentence I write, there is someone out there who will be reading this and saying, "What an idiot!" Maybe, but can you wait until I've had my say? I know there are a lot of creationists that love the catch phrase, "

Evolution is just a theory," and of course, they're missing that in the realm of science, that word tends to mean something deeper than they give it credit. Granted. What I'm saying is that even giving it all the credit it truly deserves, it's still not the end-all and be-all of truth, because science is not a religion in very important ways that are actually its

strength, but unfortunately its

lesser-known strength.

The Asimov essay that boiled over that thought was one titled "Giants in the Earth", an essay on why he thinks so many cultures (including the Bible) have had myths concerning giants and other fantastic larger-than-life creatures. He gives a number of theories about why people would imagine giants, mainly focusing on people of lesser technology who marveled at achievements of more advanced societies such as the massive walls of

Mycenae and the

pyramids of Egypt and, not being able to fathom technology that could move such massive stones, imagine the employment of giant men or sorcerers for the purpose. In general, this is not an unreasonable theory, but I do have some issues with it, the main one being the assumption that every single example of stories about giants surely could not have simply been the result of actual, living giants. After all, Goliath was only said to be nine feet tall, and while that sounds pretty fantastical, I fail to see why there could not exist a man of that stature, or at least

near that stature helped with a dash of exaggeration or rounding off to the nearest cubit. I think I may have made this exact analogy in a former piece of writing, but if a person who had never been to China or known anything about it ran into

Yao Ming, he might be tempted to tell friends that China was a land populated with giants, and he would be sort of right, since there are at least a few of them.

Now, just shortly after denying that tales of mythical giants had anything to do with

actual giants, and denying that tales of dragons could have anything to do with

actual oversized lizards such as dinosaurs or who knows what, Asimov makes this startling statement:

"The elephant bird, or aepyornis, of Madagascar still survived in medieval times. It weighed half a ton and was the largest bird that ever existed. It must surely have been the inspiration for the flying bird-monster, the 'roc,' that we find in the Sinbad tales of The Arabian Nights."

"Surely"? Maybe Asimov had some backing for this statement, but from what I see here, it seems to be pure speculation. Why does one need to go to Madagascar to find such a large bird when fairly large birds such as ostriches and crowned eagles exist on the African mainland? The apparent assertion of a matter of speculation as

bare fact is what disturbed me, and surprised me from Asimov as a supposed man of science.

Maybe it's a particular problem of Asimov's, being a writer of sci-fi and mystery, that he feels a need to see to it that loose ends are tied up into a neat little bundle. Fiction does that quite often, especially in the mystery genre. We expect when we close the book after reading the last page that even if the ending is not a happy one, we at least will have had everything

explained to us, and everything will be

understood. Religion (which atheists will gladly relegate to fictional status) also tends toward this sort of resolution. It tends to try to answer as many of the key philosophical questions of life as it can, and then blankets anything that wasn't covered with some panacea such as, "Well, God is working all things to the good, and He will triumph in the end." Everybody likes a happy ending.

Science may like to define limits, but has no end in itself, and never completely ties up all the loose ends. This is the true strength and power of science, but it's not a savory one. Those so-called skeptics who claim that science has all the answers are missing the true point of science: that it has

no answers, only a

better class of questions. The real problem of science is that people are looking for final answers, and science's disciples are more than happy to claim that they have them, despite the fact that they are (unintentionally, granted) misleading people with such a claim.

It is the

nature of science's never-ending quest to question reality that what are today's scientific

truths will be tomorrow's scientific

misconceptions. We had nine planets, but then

we only had eight. We were descended from homo erectus, but then

we weren't. The smallest indivisible units in the universe were atoms, but then they were found to be made of protons, neutrons and electrons, which were later found to be made of quarks, which in turn are made of...what? To the average person, all of this sort of stuff looks like indecision: can't science make up its mind? I thought you said science had the answers? To the non-technical mind, the answers that science give look like so much magical hocus-pocus, and when Rowling tells us in book seven that wands only properly work for their true owners, yet book four is full of magicians getting along just fine with borrowed and/or stolen wands, we start to think it may all be a bunch of crap.

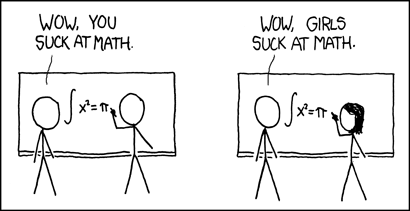

Science is suffering from bad press, and it's not bad press from those fools who do things like ban the teaching of evolution in schools, but from those people who say things like, "Science has given us the answer, and the answer is evolution." Such an attitude falls prey to those who object, "What happened to us being evolved from homo erectus?" or "Why do you think it is that

Piltdown Man turned out to just be a hoax?" If "evolution is the answer", then like dogmatic religious zealots, the disciples of the religion of science will demand that asking more questions is inappropriate, never realizing that like Pharisees berating Christ for healing on the Sabbath, they're elevating tradition over deeper, more fundamental truths. Yes, science embraces evolutionary theory, among other theories, and as a "theory" it's actually something deeper and more well-established than just an

idea of how the world might happen to work, but just as Christianity holds as an underlying tenet that "Love thy neighbor" is more important than any rules about how you run your church, science holds to an underlying tenet that above all,

we must keep asking questions of our universe.

Evolutionary theory is a better theory than its detractors give it credit, and I expect it to be a part of science for quite some time, despite the fact that simpler concepts, like the number of planets we have, lasted for much shorter time than evolution has already enjoyed. But it is the nature of science that all theories are potentially only here for today, waiting for the time that they will be replaced by a better theory and discarded. The real failure of our educational system is not a failing to convince everyone that evolution or any other theory is true; after all, the greatest scientists have always been the ones who were willing to be the first to discard the failed theories of the past. No, the real failure is not teaching our children that the real strength of science and greatness of scientists was not in their determined acceptance of the status quo, but in the very

willingness to go against it.

Mendeleyev wasn't the first person to think of the concept of the periodic table of elements (a crude approach to modern understanding of the behavior of subatomic particles before anyone had even thought of subatomic particles), but he was one of the first people to be willing to keep pushing and questioning until scientists decided to take it seriously.

Yes, the problem with science is that we haughtily insist that people accept it

as it is, forgetting that the state of science is always evolving. Religion is the one that often strives to be right without being questioned. Science? It only strives to be a little less wrong than it was yesterday, and there's nothing wrong with that.